Concerned about the impacts of fracking on biological diversity, five Smtih Fellows wrote to the U.S. Department of the Interior, the Department of Energy, and the Environmental Protection Agency to suggest research priorities on the potential environmental risks and scientific uncertainties associated with the natural gas extraction technique known as fracking.

The fracking debate hits close to home for Smith Fellow Sara Souther, a researcher at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and one of the lead authors of the letter.

As a Ph.D. student in Morgantown, West Virginia, Sara joined other citizens to urge city leaders to halt the construction of a fracking pad near the city's water supply that they believed posed health risks to residents. In the following Q&A Sara explains how her experience in Morgantown influences her today, what she learned from working with SCB's Policy Department and her scientist colleagues on the fracking letter, and why she thinks conservation biologists can do more to advance science in the public realm.

What about the public letter writing process appealed to you and encouraged you to get involved?

My involvement with hydraulic fracturing (fracking) began years ago. I was finishing my Ph.D in Morgantown, WV when I learned about construction of a frack pad a few hundred feet upstream from the intake of the city’s municipal water supply. I, along with a number of other residents, poured into public meetings to halt well pad construction. In response to the public outcry, the Morgantown City Council banned fracking within a one-mile buffer zone of town, only to have the ruling overturned by a circuit court judge just two months later.

|

|

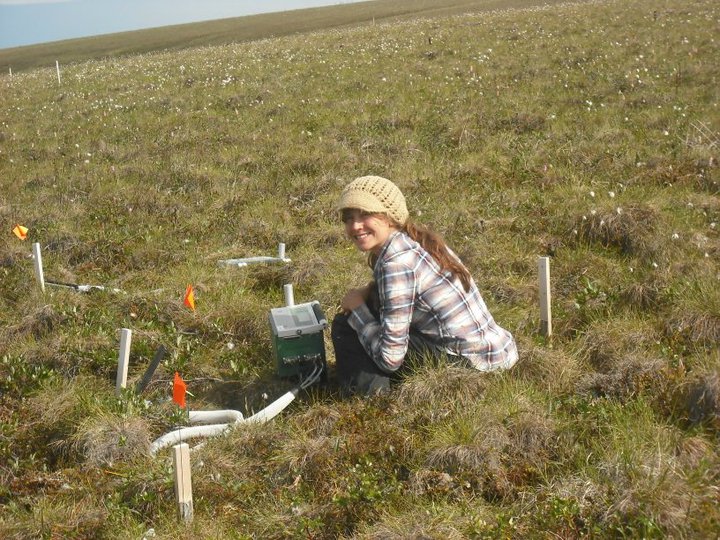

Sara measuring photosynthetic rates of Eriophorum ######### (tussock cottongrass) for a project studying the effects of climate change on the Alaskan trundra |

Political kowtowing to extractive industries is a common theme in West Virginia - one that leaves many West Virginians (myself included) feeling powerless against coal and natural gas companies. Ultimately, I was empowered to take policy-level action on hydraulic fracturing because of training during my Smith Fellowship. Brett Hartl, SCB policy fellow, mentioned that the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Department of the Interior (DOI), and the Department of Energy (DOE) were developing a prioritized research agenda to identify knowledge gaps related to fracking impacts. This created the perfect opportunity to apply my scientific expertise, as well as the group intelligence of the Smith Fellows, to highlight critical research needs and interim regulations to protect ecosystem health and biodiversity.

What one lesson/teaching point did you learn from the experience?

The most valuable thing I’ve learned is that our expertise as scientists is valued and needed in government policy work. For newcomers like me, the SCB policy program staff is an incredible resource for navigating policy-level engagement. I encourage more researchers to put their knowledge and skills to work in this arena.

What would you like to see come from the letter?

I would like to see DOI, DOE, and EPA develop a comprehensive research plan to assess the risks and impacts of fracking on ecosystem and human health. In the public sphere, industry representatives and politicians continually represent natural gas as a ‘clean’ domestic bridge fuel. However, the little research that exists on hydraulic fracturing suggests that natural gas produced in this way is anything but clean, carrying a greater carbon legacy than oil or coal, and posing a serious threat to freshwater and terrestrial resources. Before the U.S. increases its reliance on hydraulically fractured natural gas, we must understand potential ecosystem impacts. In the meantime, tighter regulations should be enacted to prevent irreversible environmental damage and attribute remediation costs and duties to those responsible.

|

|

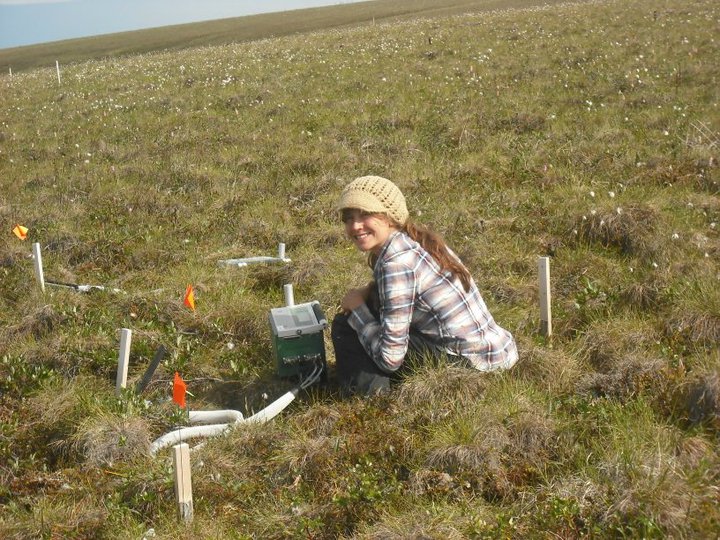

Measuring the size of understory herbs for an expirimental managed relocation project in the Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forest inWisconsin |

Would you consider getting involved in a similar manner in the future (why or why not)?

Absolutely. Every conservation biologist I know is busy, and it is all too easy to leave policy engagement to someone else – a hypothetical researcher with more time and better qualifications. I’ve realized that researcher doesn’t exist, and each of us (to the best of our ability) should take ownership over threats that impact the ecosystems that we interact with, otherwise no one will.

Why is it an effective use of your time?

For me, this experience is a win-win situation. In a best case scenario, the multiagency working group uses our letter as it develops a comprehensive research plan for assessing the environmental impacts of hydraulic fracturing. In a worse case scenario, agencies disregard our letter. Even if the latter scenario transpires, I have learned a lot about a practice that is affecting a landscape and community that I care about deeply. Using what I have learned, I will continue to raise awareness regarding the environment risks and unknowns associated with fracking through informed discussions and active sharing of research collected while drafting the letter.